There appear to be no fusilage images. Compare and contrast with this image of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie in 1988:

How open-source investigators quickly identified Iran’s likely role in the crash of Flight 752

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/01/10/how-open-source-investigators-quickly-identified-irans-likely-role-crash-flight-752/

Jan. 10, 2020 at 6:40 p.m. GMT

While Iran denies the allegation, officials who have spoken with reporters indicate that evidence exists demonstrating how the flight was targeted and received damage that prompted the plane to turn back toward its point of origin before crashing northwest of the Iranian capital.

As those authorities were sharing those conclusions, though, a team of investigators working collaboratively online had already published information strongly suggesting that this was precisely the plane’s fate. What’s more, that analysis was bolstered by photos and videos showing where the plane crashed, the moment of the apparent missile strike and even an image of the possible missile itself.

We've profiled the organization leading that effort, Bellingcat, in the past. Created by Eliot Higgins, whose work evaluating publicly available documentation of the Syrian civil war earned him international attention, Bellingcat was formed in mid-July 2014.

Days later, a Russian surface-to-air missile took down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, often referred to as MH17. Bellingcat and Higgins used photos shared online to prove, among other things, that a Russian Buk missile launcher had entered the area shortly before the crash, earning the organization and Higgins the ire of the Russian government. The organization’s research was eventually central to court cases centered on the crash.

I spoke with Higgins to walk through the process Bellingcat used to piece together what happened to PS752 outside of Tehran.

“Immediately, people start sending us photographs and links and stuff they had found online,” he said. “It was almost an involuntary crowdsourcing of the information. We, as a team, got drawn into it a bit and started looking at stuff.”

1. Crash scene photos

News of the crash was first reported publicly on Jan. 7 — Tuesday night in the United States and early Wednesday morning in Iran. When dawn broke, pictures were shared online of the apparent site of the PS752 crash. Aric Toler, Bellingcat's lead researcher for Eastern Europe and Eurasia, began trying to publicly geolocate some of the images.

Unconfirmed photo of the crash site outside of Tehran. Could geolocate it to confirm, especially with the blue-roofed building. Last ping was in vicinity of 35.501609, 50.925865 headed northwest, so search around that radius.

Direct link to orig resolution pbs.twimg.com/media/ENu3eVqW…

92 people are talking about this

Notice several things about the tweet.

First, that the image is identified as unconfirmed. Verifying images was a bit trickier in this case, Higgins said, because the sharing network popular in Iran is Telegram, with images and videos being lifted from there and shared on Twitter — possibly stripping the files of identifying information and making it harder to find the original source.

Notice, second, that Toler shares the last known position of the plane, shared by its transponder before the crash and tracked by sites like FlightRadar24.

We are following reports that a Ukrainian 737-800 has crashed shortly after takeoff from Tehran. #PS752 departed Tehran at 02:42UTC. Last ADS-B data received at 02:44UTC. flightradar24.com/data/flights/p…

4,260 people are talking about this

Third, and most importantly, notice that he’s putting the question out to the public: Can this photo be geolocated? Toler updated the thread with suggestions from followers and additional images from the scene.

Location was one issue. More important for determining the cause of the crash was imagery showing the plane itself.

“Initially, even the intelligence agencies were saying this was like an engine failure,” Higgins said. “So we were asking people to look for any photographs they found of the engines in the crash site so we could look at them and see if it supported that."

The team pored over the images they'd received, figuring out where the crash occurred and examining what was visible of the aircraft.

2. Debunking an apparent breakthrough

Part of Bellingcat’s work on MH17 was identifying a series of perforations seen in the fuselage of the wreckage of that plane. Those holes were consistent with damage from an antiaircraft missile like the Buk, given how such missiles work.

“It basically tries to create a cloud of shrapnel near the front of the aircraft that these aircraft then fly through,” Higgins explained, “rather than it being a heat-seeking missile with an explosive tip or something like that. The actual warhead's in the center of the missile; it tries to kind of spray shrapnel into the front of the aircraft.” The intended targets, after all, are meant to be “small, fast-moving jet fighters” — not “big, slow-moving airliners."

After the PS752 crash, photos of the site appeared to show similar damage. In one, taken in the early morning light, a wing is seen with marks suggesting the presence of small holes that might be consistent with shrapnel damage.

It wasn't.

“We found other images that showed that this was a low-resolution image and the dark spots were actually rocks,” Higgins said, noting that something similar had happened during the MH17 investigation. The team quickly debunked the assertion.

I've seen this image doing the rounds, with some people claiming its evidence Iranian AA shot down the Ukrainian airliner, but in my mind it's most likely to be debris from the aircraft itself that caused the damage.

173 people are talking about this

“When you're obviously dealing with a really serious incident like this, you don't want [mistakes] to happen,” Higgins said. “We've even seen various mainstream media websites using that image to say, look, here's shrapnel. Then, because we published, we noticed they'd removed these images."

“Fact-checking stuff like that might seem rather minor in the big picture, especially when it turned out it was a missile that likely shot it down,” he continued, “but you still want to actually tell the truth about these images and be clear what they are because they're part of a bigger picture that leads to our understanding of what actually happened."

The first significant evidence that the plane was downed by a missile came when the team was sent another, more evocative photo.

3. An apparent missile

The Tor is a short-range, surface-to-air missile that originated in the Soviet Union. Iran is known to possess Tor systems; a 2007 Sputnik report documented tests of some of the 29 Tors supplied to the country by Russia.

The image Bellingcat was sent showed the front end of an apparent Tor missile resting in some sort of a ditch. A bit later, they received another image taken from another angle but apparently showing the same object.

Second image (right) of Tor anti-aircraft missile debris, supposedly from near the #PS752 crash site. Still unverified, and still going to be very hard to geolocate it based on what's visible in the image. h/t @Liberalist_30

671 people are talking about this

“Unfortunately, because it was in a ditch, it didn't really show the background,” Higgins said. “So it's practically ungeolocatable based off the information that's already online."

Consider how difficult it can be to identify the location of a photograph. Take a picture outside your house and you can easily identify the scene. One somewhere in your town, a little trickier. Somewhere in an American city? You'd look for clues like signs or phone numbers or license plates. Somewhere in a foreign city? Maybe the language on signs or distinctive buildings. Somewhere in the rural part of a foreign country, showing only buildings like the ones in the photos shared by Toler? Good luck.

Now try to geolocate a piece of metal in a ditch.

“What we started looking into is whether or not those ditches were actually something you find in that area,” Higgins said. “There were pictures online from that part of Iran and we fairly quickly established, yes, you do find those kind of ditches there. So [the image] was consistent with the area — but we couldn't say it was unique to that area, because there are ditches all over the world that probably look like that. But it certainly didn't exclude it from being taken in that area, which is useful to us."

A key step in validating the image, of course, is making sure it’s not a photo re-purposed from somewhere else. In the wake of major news events, it’s often the case that people willfully or accidentally share images linked to similar events, which can muddy the issue. There are ways to identify images as having been in existence before the event at issue, like reverse image-searching (for which Bellingcat has a helpful guide). If the missile photo were taken elsewhere and earlier, the odds are good that it already exists online and might turn up in a search for similar images.

This one didn't. What's more, when that second image of the apparent missile was given to the Bellingcat team, it further suggested that the image wasn't faked.

The team still didn't have proof that this missile — or any missile — brought down PS752, however.

“Looking at the wreckage, we couldn't really see the damage we would associate with that kind of missile, similar to what we saw with MH17, where you have this kind of closely grouped pattering on the hull,” Higgins said. “But on the other hand, we weren't seeing any images of the front of the aircraft, which is where we expected to see that kind of damage. So it wasn't so much that there was evidence that proved it one way or another; it's just the evidence that we needed to do that didn't exist yet or we couldn't verify it."

And then the video turned up.

4. The video

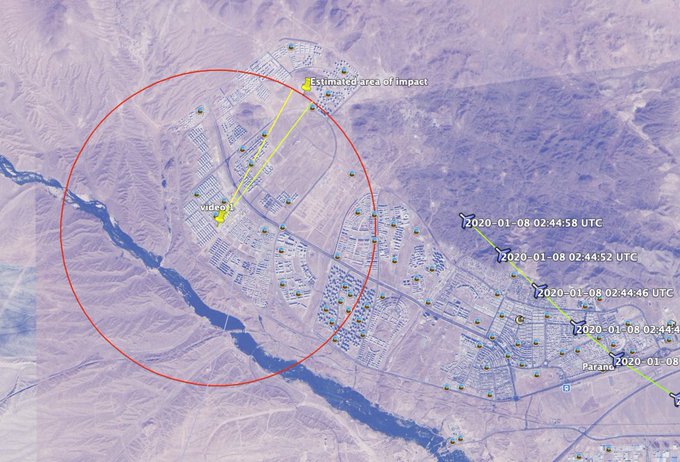

We are analyzing this new video supposedly showing a mid-air explosion. By our initial estimation, the video shows an apartment block in western Parand (35.489414, 50.906917), facing northeast. This perspective is directed approximately towards the known trajectory of #PS752.

4,511 people are talking about this

The video shows a group of buildings illuminated in yellow streetlights. There is quick streak moving through the sky and then, suddenly, a large yellow fireball. A larger yellow dot continues to move through the sky. A dog barks. There's a boom.

Higgins said that, given the work his team was already focused on, it took him a second to realize what he was looking at.

“A minute later I looked at it, and I thought, ‘Bloody hell, that seems to show the missile actually detonating,’” he said.

It didn't take long for the team to figure out the location from which the video was captured, since they'd already been focused on locating the crash site and scouring the area for ditches similar to the one seen in the apparent missile photo.

That didn't mean they immediately accepted the video as legitimate. To validate it, they used a clever trick.

It’s one which you yourself might have used in the past. Ever tried to figure out how far away lightning was by timing the gap between the flash and the sound of the thunder? The rule-of-thumb is that every five-second count between the flash and the thunder measures one mile of distance. Why? Because light travels faster than sound. The lightning’s flash gets to you almost immediately while its sound, the thunder, only moves at about 761 mph. In five seconds, sound travels 1.05 miles — so if the sound of the lightning takes 10 seconds to get to you, it’s a little more than two miles away.

The time between the flash of the apparent missile detonation and the boom heard in the video is about 11 seconds. Meaning that the detonation was about 2.3 miles or 3.8 kilometers away. Combining that information with the position of the video camera and the direction in which it was pointed allowed the team to estimate where the explosion would have taken place.

It was directly in line with the PS752 flight path.

Keep an eye out for more information coming soon via @trbrtc and his colleagues at the New York Times Visual Investigations Team:twitter.com/trbrtc/status/…

By measuring the time that it took for the camera to hear the explosion, we estimated the distance of the event (red circle), and cross-referenced it with the geolocation of the video and the flight trajectory of #PS752 (taken from from FlightRadar24).

685 people are talking about this

They weren't the only ones to connect these dots. A team at the New York Times, including Bellingcat veteran Christiaan Triebert, had similarly obtained and geolocated the video, coming to the same conclusion.

5. Completing the investigation

The video is highly suggestive of a surface-to-air missile strike, but definitive proof probably depends on finding evidence in the wreckage of the plane. That may now be impossible.

The initial images and videos the team used to identify the location of the crash are now important for another reason: The crash site has apparently been bulldozed — which Higgins described as “an extremely suspicious thing for the Iranians to do” — moving all of the debris into a big pile and probably damaging the debris as well.

“Now these initial videos that show the site before all of this happened — they’re actually increasingly valuable,” Higgins said. “What we’re doing now is trying to collect all of these videos and map them and start categorizing all the debris that’s visible because what we want to do is create a visual reconstruction of the site and the debris that was there."

It's important to see the cockpit, for example, to see evidence of possible shrapnel penetration. It's not visible in existing photographs, perhaps because it was disintegrated on impact. But, Higgins said, there also don't seem to be images of the passenger seats, which normally survive crashes intact. If the entire area has been cleared, any original photos and video may be the only way to know what survived the crash and what damage it shows.

Having learned from the MH17 investigation how material may become of legal importance down the road, Bellingcat is archiving what it collects with an organization called Syrian Archive. It also plans to contact (as it has in the past) Forensic Architecture, a research agency based at the University of London that uses geolocated evidence to create accessible, easily navigable explanations of what was found.

The PS752 crash is a tragedy and, apparently, an avoidable one. It’s also an interesting reminder of the power of the Internet and of ubiquitous recording devices. If Iran was responsible for the crash — which seems likely — and if it tried to clear the site to hide evidence — also seemingly likely — its efforts might be undone by the impulse of bystanders to record what they saw and to share it online.

Which would allow Bellingcat to continue to document and analyze it.