LOCKE

UNLOCKED: JOHN LOCKE - SCHOLAR, EXPERIMENTER, THINKER, WRITER,

TEACHER, TRAVELLER, PHYSICIAN, AND UNLIKELY REVOLUTIONARY.

A

Pensford Perspective by Tim Veater. (Part 1)

An

overview of the life and works of John Locke and it's application to

current issues of Government. (In Parts)

Preface.

This piece does not purport to be a scholarly work. Rather it attempts to cast a familiar story in a new light, highlighting the part Locke's early life and physical environment played in the making of the man and his ideas that were to have such an important impact on a world that was come after his death and of which he could have no idea. In the process it is hoped it might get a relatively small area of North Somerset, familiar to the writer, its “fifteen minutes of fame” and its most illustrious son, John Locke, his rightful place in its local history.

This is the first of several discursive pieces first published on the 'Inquiring Minds' site, which has closed with the regrettable demise of its editor Malcolm Treacher on the 21st August, 2015, who in his way, continued many of Locke's principles of 'presenting truth unto power' and to whom I should like to dedicate this edited (and hopefully corrected) version.

I have referred to a number of sources, principally the well-known biographies by Maurice Cranston and Roger Woolhouse. Others will be listed as a bibliography with the final part at a later date. The illustrations have been taken from public Internet sources, which will also be acknowledged in the final part.

If despite my best efforts and in the interests of readability, any errors have crept in or I have offended anyone, I apologise in advance and request forgiveness. The substance is all the work of others; the errors all my own.

This piece does not purport to be a scholarly work. Rather it attempts to cast a familiar story in a new light, highlighting the part Locke's early life and physical environment played in the making of the man and his ideas that were to have such an important impact on a world that was come after his death and of which he could have no idea. In the process it is hoped it might get a relatively small area of North Somerset, familiar to the writer, its “fifteen minutes of fame” and its most illustrious son, John Locke, his rightful place in its local history.

This is the first of several discursive pieces first published on the 'Inquiring Minds' site, which has closed with the regrettable demise of its editor Malcolm Treacher on the 21st August, 2015, who in his way, continued many of Locke's principles of 'presenting truth unto power' and to whom I should like to dedicate this edited (and hopefully corrected) version.

I have referred to a number of sources, principally the well-known biographies by Maurice Cranston and Roger Woolhouse. Others will be listed as a bibliography with the final part at a later date. The illustrations have been taken from public Internet sources, which will also be acknowledged in the final part.

If despite my best efforts and in the interests of readability, any errors have crept in or I have offended anyone, I apologise in advance and request forgiveness. The substance is all the work of others; the errors all my own.

The Monmouth Uprising 1685.

HARSH TIMES: "It is said that at this time there was not a crossroads in Somerset that was not splashed with the blood of the rebels. This was not isolated to Somerset, the remains of one individual that were sent to Tiverton remained there for over 3 years!"

1. Introduction.

John Locke, FRS (1632 –

1704), the seventeenth Century philosopher, is regarded as one of the

earliest and most influential thinkers in the English-speaking world.

Building on the approach of others, such as Francis Bacon (1561 –

1626) and the Frenchman Rene Descartes (1596 – 1650), he asserted

the primacy of reason in matters of natural philosophy, religion,

politics and man himself. As such he is considered to be one of the

first of the British “empiricists”.

In turn he influenced later thinkers including Voltaire (1694 – 1778) , Rousseau (1712 – 1778) , David Hume (1711 – 1776) and Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) amongst others.

He also had a direct impact on British and American political development, specifically the British “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 and the American Revolution of 1776. Many of his ideas were pillars of both the United States Declaration of Independence and first Constitution.

To this liberal philosophy, was added his consideration of the mind, holding that all children were born as it were with a blank slate ("Tabula Rasa") and were shaped by environmental forces, to become what they were as adults, emphasising perception and experience.

In consequence, in both the political and religious spheres, whilst maintaining an outwardly very conservative stance, he challenged some deeply embedded philosophical ideas such as original sin, predestination, divine right of kings to govern, the duty of the subject to obey, and even the nature of the Christian God itself! In a wider sense he contributed to the “Enlightenment”, from which sprang later scientific discovery and democratic principles of government.

He wrote and was published, always anonymously, in the latter quarter of the 17th Century, and it was only a good deal later and largely after his death in 1703 that their importance was fully recognised and his name attached to them.

He was in a way one of what we might regard as one of the last old-style polymaths, interested in, and by the standards of the time, expert in, a range of spheres of human knowledge and endeavour, there being then no great divide between the arts and sciences or between religious or secular views of the world. Most of the intellectual debate centred on differences in religious interpretation of the Bible and how this should apply to practical living and government.

It is hard now to appreciate the revolutionary nature of Locke's thinking and argument the effect of which was to challenge both temporal and spiritual perceptions and man's place in them. We have to realise that the metaphysical world of the Elizabethan was a very real one, filled with angels of light, dark spirits and the physical reality of a Divine being and eternal damnation or bliss experienced by the human soul.

We should resist the temptation to be historically superior about this as we are daily reminded these attitudes and beliefs persist in millions of people about the world. However Locke with a few others, was one of the first to subject knowledge to a new 'empirical' approach subjecting everything to examination and challenge, using reason alone. The Frenchman Rene Descarte famously coined the phrase 'Cogito ergo sum' (I think therefore I am) as his starting point, and Locke who was greatly influenced by him, took up his Socratic method.

So in the time time between Locke's grandfather's arrival in Pensford in the late 16th Century and Locke's death at the beginning of the 18th, a great transformation, revolution in fact, had taken place, though not generally recognised by the general population, first and foremost concerned with the details of their daily lives.

Locke's life was dominated by the turbulent events of the time, first Civil War and Interregnum that established in the political sphere the primacy of Parliament over the Crown and then another political crisis in which he was intimately involved, termed the 'Glorious Revolution', that set in stone a Protestant succession and limits on the Monarch's powers.

So Locke's ideas were born out of revolution. Little did he know the impact on further, arguably greater ones, for his ideas figured large in the writings of people like Voltaire and Thomas Paine that fired the political upheavals in the British American colonies and Republican France.

The illustration below represents a time when Locke's grandfather arrived in Pensford in the latter part of the sixteenth century and perhaps slightly more obliquely a world view that was transformed by Locke and his generation. John Dee (1527 - 1608/9) influential advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, is emblematic of the old school of thinker and of the great divide between him and Locke. He was (in the words of the WIKI entry) "a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occult philosopher, imperialist who devoted much of his life to the study of alchemy,divination and Hermetic philosophy and in the last thirty years or so of his life to attempting to commune with angels and demons in order to learn the universal language of creation and bring about the pre-apocalyptic unity of mankind"! Even though superstition still reigned in the 18th Century, as indeed it still does today in certain quarters, Locke had indeed ushered in a new and rational enlightenment that was to have unlimited consequences for mankind.

In turn he influenced later thinkers including Voltaire (1694 – 1778) , Rousseau (1712 – 1778) , David Hume (1711 – 1776) and Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) amongst others.

He also had a direct impact on British and American political development, specifically the British “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 and the American Revolution of 1776. Many of his ideas were pillars of both the United States Declaration of Independence and first Constitution.

To this liberal philosophy, was added his consideration of the mind, holding that all children were born as it were with a blank slate ("Tabula Rasa") and were shaped by environmental forces, to become what they were as adults, emphasising perception and experience.

In consequence, in both the political and religious spheres, whilst maintaining an outwardly very conservative stance, he challenged some deeply embedded philosophical ideas such as original sin, predestination, divine right of kings to govern, the duty of the subject to obey, and even the nature of the Christian God itself! In a wider sense he contributed to the “Enlightenment”, from which sprang later scientific discovery and democratic principles of government.

He wrote and was published, always anonymously, in the latter quarter of the 17th Century, and it was only a good deal later and largely after his death in 1703 that their importance was fully recognised and his name attached to them.

He was in a way one of what we might regard as one of the last old-style polymaths, interested in, and by the standards of the time, expert in, a range of spheres of human knowledge and endeavour, there being then no great divide between the arts and sciences or between religious or secular views of the world. Most of the intellectual debate centred on differences in religious interpretation of the Bible and how this should apply to practical living and government.

It is hard now to appreciate the revolutionary nature of Locke's thinking and argument the effect of which was to challenge both temporal and spiritual perceptions and man's place in them. We have to realise that the metaphysical world of the Elizabethan was a very real one, filled with angels of light, dark spirits and the physical reality of a Divine being and eternal damnation or bliss experienced by the human soul.

We should resist the temptation to be historically superior about this as we are daily reminded these attitudes and beliefs persist in millions of people about the world. However Locke with a few others, was one of the first to subject knowledge to a new 'empirical' approach subjecting everything to examination and challenge, using reason alone. The Frenchman Rene Descarte famously coined the phrase 'Cogito ergo sum' (I think therefore I am) as his starting point, and Locke who was greatly influenced by him, took up his Socratic method.

So in the time time between Locke's grandfather's arrival in Pensford in the late 16th Century and Locke's death at the beginning of the 18th, a great transformation, revolution in fact, had taken place, though not generally recognised by the general population, first and foremost concerned with the details of their daily lives.

Locke's life was dominated by the turbulent events of the time, first Civil War and Interregnum that established in the political sphere the primacy of Parliament over the Crown and then another political crisis in which he was intimately involved, termed the 'Glorious Revolution', that set in stone a Protestant succession and limits on the Monarch's powers.

So Locke's ideas were born out of revolution. Little did he know the impact on further, arguably greater ones, for his ideas figured large in the writings of people like Voltaire and Thomas Paine that fired the political upheavals in the British American colonies and Republican France.

The illustration below represents a time when Locke's grandfather arrived in Pensford in the latter part of the sixteenth century and perhaps slightly more obliquely a world view that was transformed by Locke and his generation. John Dee (1527 - 1608/9) influential advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, is emblematic of the old school of thinker and of the great divide between him and Locke. He was (in the words of the WIKI entry) "a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occult philosopher, imperialist who devoted much of his life to the study of alchemy,divination and Hermetic philosophy and in the last thirty years or so of his life to attempting to commune with angels and demons in order to learn the universal language of creation and bring about the pre-apocalyptic unity of mankind"! Even though superstition still reigned in the 18th Century, as indeed it still does today in certain quarters, Locke had indeed ushered in a new and rational enlightenment that was to have unlimited consequences for mankind.

John Dee and Queen

Elizabeth I

Locke

Remembered and Relevant?

Not everyone will be

familiar with Locke or his writings, even though they have had a huge

and lasting influence on our lives. Philosophers, past or present,

get scant regard from current society. Locke's memorials are few and

scattered. Apart from his printed works and biographies, they are

limited to a few busts, plaques and portraits in inaccessible

locations. There is a bust and plaque in Wrington Church, an epitaph

at High Laver, Essex and a memorial stone in the floor of Christ

Church, Oxford. As far as I am aware, there was until recently, no memorial in his Pensford home. One of the lights in the Millennium Window in Publow Church now commemorates his life. It reminds me of the biblical saying: “A

prophet is not without honour, save in his own country”.

The Wrington House where he was born (now demolished)

And the bust of him that remains in the porch of Wrington Church, Somerset.

The Wrington House where he was born (now demolished)

And the bust of him that remains in the porch of Wrington Church, Somerset.

Tomb at High Laver, Essex.

Plaque at Christ Church, Oxford

However, his reasoning has never been more relevant to modern issues and controversies. The current debate on the relationship between citizen and government, in an age of over-arching power to monitor and control, has been awoken from its slumbers by the activities of Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and others.

There is a growing awareness of how by stealth and the pretext of danger, Western Governments and Corporations have extended their remit to pry into the lives of ordinary people, and increased their legal powers to intervene and control, with little to stop them doing so. As Noam Chomsky wrote recently to the American web site“Counter Punch”:

“It is, regrettably,

no exaggeration to say that we are living in an era of irrationality,

deception, confusion, anger, and unfocused fear — an ominous

combination, with few precedents. There has never been a time when

it was so important to have a voice of sanity, insight, understanding

of what is happening in the world.”

Revolutionary

Times.

The period Locke lived

through was not without its momentous events, bloody conflicts and

political developments, as ideas clashed with ideas and cohort with

opposing cohort. He later recorded: “I no sooner perceived myself

in the world but I found myself in a storm, which has lasted almost

hitherto.” (1660)

King against

Parliament. Town against Country. Merchant against Aristocracy.

Levellers versus those that believed in hierarchy. Rich against poor.

Tolerance versus Conformity. Superstition versus Reason. Protestant

against Catholic. Anglican versus Non-conformist. Puritan versus

Quaker and Shaker. “Whig” versus “Tory”. Stuart line versus

House of Orange replacement.

An indication of the

parlous state of the County of Somerset caused by civil war (no doubt replicated

throughout the country) is illustrated in this passage from the

Somerset Rolls. Note how certain individuals disadvantaged by Royal troop actions directed at one of Popham's principal estates in Wellington, Somerset were ordered to be compensated by magistrates, of which Popham was one, representing the now victorious Parliamentary faction.

In addition heavy levies were demanded for paying off the debts incurred by the State and providing the armies to be raised for Scotland and Ireland. On the other hand, the paying power of the County was much diminished. Few districts can have seen more of hostile armies, and the flocks and herds of the countryside had been consumed. Without oxen the land could not be cultivated, and the farmers could pay neither rents nor rates. Even when rents, or a portion, were forthcoming, the royalist landowner had to send them to London to discharge the fines levied for his malignancy.

For some years the financial difficulty was always present and acute. Sir John Berkeley, afterwards Lord Berkeley of Stratton, who in a few days put the business in very good order, and by storm took Wellington House early in the month of April. (Clarendon, Book IX.) Some of the townspeople had placed their goods in the house for safety. A certificate was given by Richard Bovett and Alexander Popham on the 1 9th October, 1650, that Anne Martyn of Wellington, widow, suffered loss of cattle and household goods to the value of 175/2". besides 22/2. in money and the loss of her eldest son, they all being in the house of the Honorable Alexander Popham at the siege thereof by the late king's forces. (S.R., 82, i, 14.) At Taunton, 1655, she was allowed ten shillings for the present, and at Taunton, 1556, twenty shillings for the present.

Mary (Maud) Cape petitioned at Bridgwater, 1646, for maintenance for herself and children, as her husband had been slain at Wellington House in the State's service (p. 5). Eventually the parish of Wellington was ordered to pay her a weekly allowance of one shilling ; and she continued to petition and to receive small sums for several years. At the Wells Sessions, 1647-8, the widow Hickman of Wellington, whose husband was slain in the Parliament service, was allowed twenty shillings for present relief and to take her home again (p. 53)."

Sir John Berkeley, afterwards Lord Berkeley of Stratton, who in a few days put the business in very good order, and by storm took Wellington House early in the month of April. (Clarendon, Book IX.) Some of the townspeople had placed their goods in the house for safety. A certificate was given by Richard Bovett and Alexander Popham on the 1 9th October, 1650, that Anne Martyn of Wellington, widow, suffered loss of cattle and household goods to the value of 175/2". besides 22/2. in money and the loss of her eldest son, they all being in the house of the Honorable Alexander Popham at the siege thereof by the late king's forces. (S.R., 82, i, 14.) At Taunton, 1655, she was allowed ten shillings for the present, and at Taunton, 1556, twenty shillings for the present. "

http://archive.org/stream/somersetpub28someuoft/somersetpub28someuoft_djvu.txt

Religion and the role

of the King which were inextricably linked, were dominant themes. On

the one hand, the belief all executive power resided in the Monarch

who obtained such authority from the Creator itself; on the other,

that power resided ultimately in the people. It, and the power to tax

without Parliamentary consent, was at the root of the civil war that

lasted, on and off, for most of the 1640's - until King Charles I

lost his head on a bitterly cold January morning in 1649.

Regicide – a crime so unthinkable, the crowd let out, what an observer described as, “a moan as he had never heard before and desired he might never hear again". Handkerchiefs were dipped in the king's blood as a memento and such “revered” artifacts survive to this day. It is even possible that Locke and the other Westminster scholars, despite the efforts of the Headmaster, heard the groan!

Regicide – a crime so unthinkable, the crowd let out, what an observer described as, “a moan as he had never heard before and desired he might never hear again". Handkerchiefs were dipped in the king's blood as a memento and such “revered” artifacts survive to this day. It is even possible that Locke and the other Westminster scholars, despite the efforts of the Headmaster, heard the groan!

Locke's life also

spanned an absolutely pivotal period in human exploration,

colonisation and experimentation. It effectively marks the start of

science as we know it, which progressively affected humanity's world

view. From being central to the divine creation and plan, both

literally and metaphorically, the role God played was gradually

pushed back by discoveries through microscope and telescope, by

observation, measurement, experiment and exploration. Having created

the “clock”, God was likened to the Clock Maker.

The Royal Society, the world's first truly scientific body, and to which Locke was elected in ...., is currently celebrating the 350th anniversary of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first to reveal, by use of the newly invented 'microscope' the secret and fantastic world of the very small. It represents the other extreme of Galileo's exploration of the very large and distant.

The Royal Society, the world's first truly scientific body, and to which Locke was elected in ...., is currently celebrating the 350th anniversary of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first to reveal, by use of the newly invented 'microscope' the secret and fantastic world of the very small. It represents the other extreme of Galileo's exploration of the very large and distant.

The Bible account was

being tentatively challenged. From the fundamentalist literal view of

the Bible, Locke moved inexorably towards a nuanced and deist

interpretation by virtue of his own reasoning, whilst still retaining

an evangelical view of Jesus as redemptive Christ and Saviour. Reason

versus Faith or conversely Reason supportive of Faith, resulted in a public debate with clerical opposition in his later years.

In Italy in 1642, when

Locke was ten, in far-off Italy, Galileo Galilei, who had been forced

by the Catholic Church's Inquisition to recant his assertion that the

sun, not the earth, was at the centre of the solar system, died. In

the very same year, the great Isaac Newton was born. These two

historical figures mark a huge transformation from the old to the

new, what may be described as a scientific and religious revolution.

The first truly

scientific society – the English Royal Society, still of course in

existence - was founded in 1660, composed of some of the most

enquiring minds of the day. Among the original Fellows were

Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, Robert Boyle, and Robert Hooke. Some

later notables were John Flamsteed, Edmond Halley and Hans Sloane.

John Locke was to be elected to Fellowship in 1668 and moved in these

circles. Whilst on Somerset trips in the mid-1660's, Locke contributed

directly to Boyle's experiments on pressure, working out of Strachey's Sutton Court to local high points on Clutton Hill, and he was an assiduous

collector of meteorological information, taking rain and other weather readings every day for the greater part of his life. This was the new scientific approach in action that was to be replicated by many others subsequently.

He was interested in

all things human and all things scientific, what was then referred to

as Natural Philosophy.

He was well versed in the Classics, could speak at least seven

languages and was fascinated with archaeological remains as with the

pre-historic Stanton Drew Stone Circle close to his home that he

described and discussed with John Evelyn. He was a respected lecturer

and tutor in Latin and Greek, a trusted surgeon and physician, a

confidant and adviser to political activists at the highest level.

Described by a friend as a “man with a versatile mind” and today

recognised as an early polymath when knowing “something about

everything” was still a possibility.

Robert

Hooke's Microscopic Flea and Isaac Newton's Telescope.

Galileo's Telescope 1610 (Source: http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/images/I012/10315150.aspx)

But Locke is chiefly remembered for his philosophical writings on economics, government and education at a time of great political upheaval and growth in trade, commerce, technical innovation and global expansion east and west. In all of these Locke had a prominent and direct involvement. Furthermore it now appears that the writings for which he famous published in or about 1690, were in fact drafted in the early 1660's which equates to an extended stay in Somerset when his father was ill. So it it is not altogether fanciful that Locke's influential ideas were conceived in Pensford air and writings with a quill dipped in Pensford ink!

A full bibliography of his works can be found here:http://www.libraries.psu.edu/tas/locke/bib/ch0.html We hope to discuss them more fully later.

But Locke is chiefly remembered for his philosophical writings on economics, government and education at a time of great political upheaval and growth in trade, commerce, technical innovation and global expansion east and west. In all of these Locke had a prominent and direct involvement. Furthermore it now appears that the writings for which he famous published in or about 1690, were in fact drafted in the early 1660's which equates to an extended stay in Somerset when his father was ill. So it it is not altogether fanciful that Locke's influential ideas were conceived in Pensford air and writings with a quill dipped in Pensford ink!

A full bibliography of his works can be found here:http://www.libraries.psu.edu/tas/locke/bib/ch0.html We hope to discuss them more fully later.

A

Pensford Perspective

I have always felt a

special affinity with, and respect for, John Locke. Not because I

compare myself intellectually of course, but simply because his

character, writings, and positive influence on history are so

impressive and because though separated by three hundred years, there

were elements of commonality between his formative years and my own.

Not least that he spent them in the same village, and was subject to

a not dissimilar religious background.

Incredibly, the local schools I attended, at no time pointed out the link Locke had with the area or his international status and impact. I had to discover it for myself and despite the fact he now has a somewhat higher profile locally, he still lacks an appropriate and tangible memorial.

Incredibly, the local schools I attended, at no time pointed out the link Locke had with the area or his international status and impact. I had to discover it for myself and despite the fact he now has a somewhat higher profile locally, he still lacks an appropriate and tangible memorial.

Daily, on the school

bus run, we slowed to negotiate the narrows, bordered by high

limestone walls, behind which were set two large and distinguished

houses - to me, always a touch mysterious and unapproachable.

Little did I realise in one of these locations the great John Locke grew up and later inherited an estate that surrounded it. That he had been familiar with the same woods and fields, the same buildings and landscape, swam and fished in the same river and walked the same winding lanes, creates a ephemeral but tangible emotional link. Both my grandfathers owned freeholds that had belonged to Locke centuries before, as do I!

Little did I realise in one of these locations the great John Locke grew up and later inherited an estate that surrounded it. That he had been familiar with the same woods and fields, the same buildings and landscape, swam and fished in the same river and walked the same winding lanes, creates a ephemeral but tangible emotional link. Both my grandfathers owned freeholds that had belonged to Locke centuries before, as do I!

A Somerset Home.

Wrington

All the biographies observe John Locke's birthplace as Wrington, Somerset in 1632. It is true but also somewhat misleading, in that it tends to suggest the Wrington house (illustrated below) was his family home and childhood environment. It wasn't. It was his mother's grandparent's home, a very modest affair at the north entrance to the majestic parish church of All Saints. (It is one of those little coincidences that Publow Church closely linked to the Locke/Popham estates is also “All Saints”) He was there just long enough to be baptised by the local puritan and non-conformist Rector, Dr Crook, after which he returned home to Pensford, where he spent the next fifteen years, maintaining links until he died.

Loke's birthplace. Compare and contrast with photo above.

Belluton

Locke's family home was

some ten miles or so to the east, in a small hamlet called Belluton,

mentioned in the Doomsday Book of 1086, just outside the market town

of Pensford and five miles south of the important commercial city of

Bristol.

Facsimile

of the Doomsday Entry

The hamlet of Belluton

consists today of two substantial 18th and 19th

Century houses, probably on the site of earlier ones, two significant

farm houses with outbuildings and numerous smaller houses and

cottages and the attached enclosed fields one of which is still

called “Locke's Cottage”.

The

View from above Locke's house today

The house sits on

elevated ground falling away to the south and the River Chew, with

fine views to the Mendip Hills beyond. Behind and to the north the

land rises to a limestone promontory, on which there is an Iron Age

fort known as 'Maes Knoll', complete

with burial mound and earth works. So in a way the situation of the

house replicated the social status of the family that lived in it –

neither too high nor too low.

In

the post-Roman period, when Britain was a patchwork semi-kingdoms,

Maes Knoll formed part of a quite incredible defensive earth work

that ran from the Bristol Channel to Salisbury called the 'Wansdyke'.

This virtually formed the north-easterly boundary of the Locke land.

Ordnance Survey Map

of Maes Knoll and part of the Wansdyke

Pensford

“It has a character, and a good one; could any tiny place be more crowded with quaint loveliness? Perhaps we found it at its best, for it was a glorious spring day and the Aubrietia was creeping down the stone walls through which the river runs, ten feet down from the cottage gardens to the water, and it is all bridges- three little stone ones and a colossal viaduct dwarfing the village, the tower, the roofs and everything with its 16 great arches carrying the trains 100 feet up in the air. A perfect miniature is the little domed lock-up looking down the street. Wandsdyke which runs close by is hardly noticed.”

“The 14th century church is nearly moated with the little river; in its long history the nave has been flooded four feet deep. It has a 15th century font with quatrefoils and roses; a Jacobean pulpit of which every inch is carved with swaures and circles and leaves, and in the tower we found an odd little man most certainly winking, though winking at nothing we could see.

“In this small place there lived two people whose son was to join our immortals, father and mother of our philosopher John Locke.”

It appears it had always been so regarded, because in 1542 Henry VIII's roving inquisitor, Leland described it as ‘a “praty” (pretty?) townlet much occupied in clothiage, with a market and a stream which flows down to it and drives several fulling mills’.

Pensford Today

Belluton, as can be

seen from the Ordnance Survey map below, is situated just to the

north of Pensford, which in Locke's time was a small town, somewhat in decline. Two

or three hundred years previously, it had been one of the most

important Somerset centres for the production of high quality 'broad-cloths', with Royal Charters for a weekly market and twice annual

fairs and ancillary industry utilising the water power provided by

the River Chew and surface coal mining in local fields.

Pensford is not mentioned in Doomsday and was not even a unit of taxation in 1327 or 1334. It never became a parish in its own right, although the Church of St Thomas a Beckett – a Chapel of Ease of the Parish Church at Stanton Drew - has recently been shown to have been in existence as early as 1320. Belluton referred to above and most of the Locke estate, was situated up until the 19th Century in the parish of Stanton Drew, when it was incorporated into an enlarged one of Publow which included the Pensford settlement.

The anomaly of a divided town between ecclesiastical and civil parishes resulted from predating topography using the River Chew as the natural dividing line between the two halves. This may well have had a detrimental effect on the development of self-governance for the town, as happened in so many other commercial towns in the post Norman period. Typically, if the inhabitants were prosperous and trade flourishing, the market and fair charters would be complimented by borough status and an element of self governance with Mayor, Aldermen and other official looking after things corporate.

This did not happen in Pensford, and although having the markets and fairs, these were governed and controlled by either Church or Manorial Lords, of which the Pophams and Lockes were 17th Century examples.

The later medieval period had seen the town at the zenith of its prosperity. In 1395/6, it was the largest cloth market in the county, registering a fifth of the county’s cloth and more was produced in Somersetshire than any other! The Charters had been obtained by the monks of Keynsham Abbey, which later fell foul of Henry VIII and his over-zealous Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell and then passed to the Lords of the Manor.

From that time, with the cloth industry moving north and competition from abroad it was a story of steady decline. Even so its track record in cloth was probably the reason Locke's grandfather grand father, Nicholas a wealthy cloth merchant, had relocated to Pensford from Dorset late in the reign of Elizabeth I. Maybe having made his money in cloth he decided to reinvest it in land where cloth had been a major industry and skills still existed, should it revive. Who knows?

Pensford is not mentioned in Doomsday and was not even a unit of taxation in 1327 or 1334. It never became a parish in its own right, although the Church of St Thomas a Beckett – a Chapel of Ease of the Parish Church at Stanton Drew - has recently been shown to have been in existence as early as 1320. Belluton referred to above and most of the Locke estate, was situated up until the 19th Century in the parish of Stanton Drew, when it was incorporated into an enlarged one of Publow which included the Pensford settlement.

The anomaly of a divided town between ecclesiastical and civil parishes resulted from predating topography using the River Chew as the natural dividing line between the two halves. This may well have had a detrimental effect on the development of self-governance for the town, as happened in so many other commercial towns in the post Norman period. Typically, if the inhabitants were prosperous and trade flourishing, the market and fair charters would be complimented by borough status and an element of self governance with Mayor, Aldermen and other official looking after things corporate.

This did not happen in Pensford, and although having the markets and fairs, these were governed and controlled by either Church or Manorial Lords, of which the Pophams and Lockes were 17th Century examples.

The later medieval period had seen the town at the zenith of its prosperity. In 1395/6, it was the largest cloth market in the county, registering a fifth of the county’s cloth and more was produced in Somersetshire than any other! The Charters had been obtained by the monks of Keynsham Abbey, which later fell foul of Henry VIII and his over-zealous Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell and then passed to the Lords of the Manor.

From that time, with the cloth industry moving north and competition from abroad it was a story of steady decline. Even so its track record in cloth was probably the reason Locke's grandfather grand father, Nicholas a wealthy cloth merchant, had relocated to Pensford from Dorset late in the reign of Elizabeth I. Maybe having made his money in cloth he decided to reinvest it in land where cloth had been a major industry and skills still existed, should it revive. Who knows?

Ordnance Survey Map

of Pensford, Somerset.

Publow

The

town of Pensford was divided between two ecclesiastical and civil

parishes roughly demarcated by the River Chew and “Salter's Brook”.

To the west Stanton Drew and to the east Publow. Land ownership and

proprietorial rights are complicated but roughly followed a similar

geographical division.

All land was vested in the King but could be held in various

capacities by his subjects from “freehold” through”leasehold”

to various states of rental occupation. Lords of the Manor roughly

followed the civil parishes. That of Publow was vested in Col

Alexander Popham and leased to the Lockes, probably in recognition of

John Locke Senior's support for him in the Civil War. (It was

in Publow Church in 1642 John Locke stood during Divine Service to

declare for the Parliamentary Side which must have caused quite a

stir.) Popham

was based in Wiltshire but had estates elsewhere including Publow and

Wellington, near Taunton and was a Justice of the Peace, of which

more later. Locke's father was Clerk and Steward for him.

Stanton

Drew

Stanton

Drew's 15th

Century Bridge

To the west, was

located the Bronze Age Stanton Drew Stone Circles, the purpose and

significance of which, by the time of Locke, had been lost in

antiquity. Whether social, political, religious or astronomical, and

probably something of each - it remains an impressive memorial to a

lost civilisation, replicated at Avebury, Stonehenge and numerous

locations throughout the western British Isles and France. Recent

excavation and geological mapping have indicated a much more ancient

and complicated history of multiple wood henge illustrated below, of

which Locke was unaware of course.

The Stanton Drew

Stone Circle and recently discovered Post Holes.

He would however, been

very much aware of local interpretations and superstitious legends

attached to them such as the familiar story of the dancers turned to

stone for disregarding the Sabbath, which must have conveyed mixed

emotions to Locke himself.

The question of tolerance and the right of the Church to impose behavioural restrictions on the one day free of work was a burning question nationally and locally in the 17th Century. Puritan Rector Crook in Wrington had actually engaged in litigation to stop Sunday games which required the direct intervention of the King no less, to annul. It was a confrontation in miniature of a national debate, akin to what we see in Muslim states today. In England in the 1660's, over a decade of Christian fundamentalism was placed in abeyance by popular demand by the Restoration although Puritanism and other off shoots such as Congregationalists, Unitarians, Baptists and Quakers continued to flourish, all well represented in the region.

The question of tolerance and the right of the Church to impose behavioural restrictions on the one day free of work was a burning question nationally and locally in the 17th Century. Puritan Rector Crook in Wrington had actually engaged in litigation to stop Sunday games which required the direct intervention of the King no less, to annul. It was a confrontation in miniature of a national debate, akin to what we see in Muslim states today. In England in the 1660's, over a decade of Christian fundamentalism was placed in abeyance by popular demand by the Restoration although Puritanism and other off shoots such as Congregationalists, Unitarians, Baptists and Quakers continued to flourish, all well represented in the region.

The Sunday Revellers

“turned to stone”.

As part of a 16th

Century scientific awakening, these sites were provoking a systematic

archaeological investigation and theorising, which Locke, having them

on his very doorstep, engaged. Correspondence survives between him

and John Aubry, an early antiquarian. Can there be any doubt that

surrounded by these ancient features, Locke's imagination and

curiosity must have been cultivated?

The Family Home

As regards the family

home, it was much superior to the Wrington cottage, in which he saw

the light of day. It was probably a Tudor Farmhouse, neither grand

nor modest. It had been purchased by his grandfather Nicholas and

handed on to his father, John senior. It consisted of a parlour,

hall, study, kitchen, buttery, three (bed) chambers and outside,

stables, all with furniture and fittings. Perhaps, the most

significant item in the the still extant inventory, is reference to a

library containing books to the value of £5:14:0. This when a stool

was valued at 6d and even an exclusive clock was valued at £2:0:0 indicates the family's attitude to reading and education. This was no working class household then, and it is clear from the

first, Locke was brought up in a bookish, puritanical and politically

aware household.

Belluton House today

– probably the location of Locke's House

His was a fairly

prosperous, low-church, family of which he was the third generation

that had made it's money, like so many others, from the clothing

trade and latterly from land and employed occupation. His father was an attorney, JP's Clerk and steward for the

local Lord of the Manor and for fledgling local government.

Locke had a brewer

uncle in Bristol, five miles distant, a cosmopolitan and maritime

port and city with strong links to the West Indies and the triangular

slave trade; coal mines on his father's land; a fascinating

topographical and historic environment; direct connections with both

local and national events; a serious Puritanical world view. All

these things contributed to shaping Locke's early character.

So Locke was not, and

never became a member of the aristocracy, but in a rural community, he decidedly was

not one of the labouring classes and occupied a privileged and

elevated status carved out by his father and grandfather. It is fair to assume he was treated with a fair degree of respect and circumspection locally by virtue of his father's role as landlord, Justices Clerk and agent for the Popham Lords of the Manor, but this was not so impressive a background when he found himself walking in the corridors of power, where he would be treated very much the educated commoner.

That is not to say his family was completely lacking in the sort of status and breeding that might impress the class conscious Jacobean. He was able to trace his lineage to Sir William Locke, mercer to Henry VIII, alderman and sheriff of London in 1548. Locke was therefore fortunate in possessing a good springboard from which to jump and could be proud of his ancestral line, confirmed by the fact that he adopted Sir William's arms for his own seal. Such distinctions, then as now, could be of critical importance to an individual's social advance.

That is not to say his family was completely lacking in the sort of status and breeding that might impress the class conscious Jacobean. He was able to trace his lineage to Sir William Locke, mercer to Henry VIII, alderman and sheriff of London in 1548. Locke was therefore fortunate in possessing a good springboard from which to jump and could be proud of his ancestral line, confirmed by the fact that he adopted Sir William's arms for his own seal. Such distinctions, then as now, could be of critical importance to an individual's social advance.

It was in Pensford that Locke

remained, until his fifteenth year, when he experienced a huge change in his life circumstances when he was dispatched to London for

schooling. He returned periodically thereafter and may even have

drafted some of his later works in the Belluton home whilst waiting for the fetid political atmosphere to cool with the death of Oliver Cromwell and return of Charles II. His views on the infallibility of the monarch, the need for religious toleration and separation from civil government, the continuing dangers of Catholicism and principles of democratic accountability, were probably beginning to be formed at this time. On the death of his father in February

1663 at only fifty- seven, Locke inherited the estate of property and

land, delayed for four years to pay off debts accrued, providing a

moderate income of around fifty pounds, for the rest of his life.

A

scholarly discussion and description of Locke's 17th

Century property portfolio by Roger Woolhouse, a recent biographer is

available on the web at:

For

someone like myself,

growing up in the immediate vicinity, it of course holds a particular

fascination. A map (by kind permission of the Ordnance Survey) indicates the extent of Locke's portfolio. Belluton house

is unfortunately just out of view immediately north of Pensford

village. The Locke estate, either held freehold or on a 99 year lease

from Alexander Popham, extends to about eighty acres east and west,

north and south, of the Pensford settlement in recent times approximating to the farms of Guys, Grange and Belluton Farms although recent land sales have changed this.

Friends

and Family

For the times, the

Locke family was small. His mother Agnes (nee Keene) was actually

nine years older than his father, and gave birth to only three

children, one of which did not survive.

Both John and his younger brother by five years, Thomas, were rather delicate. Thomas followed him to Westminster School, but did not excel and succumbed to probably plague when still only 26. In fact both father and brother died in the same year, 1663, when Locke was thirty-one. His mother Agnes had already passed away in 1654 so at thirty-one, Locke remained the only survivor, bereft of paternal, maternal or sibling advice or support and suffering from asthma type symptoms. One of his uncles, Peter, provided indispensable help looking after the estate when John was living and working away.

Both John and his younger brother by five years, Thomas, were rather delicate. Thomas followed him to Westminster School, but did not excel and succumbed to probably plague when still only 26. In fact both father and brother died in the same year, 1663, when Locke was thirty-one. His mother Agnes had already passed away in 1654 so at thirty-one, Locke remained the only survivor, bereft of paternal, maternal or sibling advice or support and suffering from asthma type symptoms. One of his uncles, Peter, provided indispensable help looking after the estate when John was living and working away.

Now as to the first

fourteen years of Locke's life in Pensford, (photo below) his

character, activities and acquaintances, we have relatively sparse

information. To a certain extent we have to fill the gaps with

reasonable supposition. So we get a picture of a small family unit

with rather stern and distant puritan parents taking their religion

and politics seriously. Father busy and cerebral effectively

fulfilling the role of a local authority, police authority, water

authority, highways agency, social security, inland revenue and

administrator of justice all rolled in one. Queen Elizabeth I had

identified JP's as her effective administrative arm a century before.

Women were publicly whipped in Pensford for falling pregnant outside

marriage for example. Locke's father was specifically responsible for

the county's sewers and for calculating and collecting the hated Ship

Money – one of the aggravating factors leading up to the civil war.

Pensford was part of the Popham estate, for which John senior acted

as attorney. It was the location of a weekly market and twice yearly

fair that required supervision and adjudication.

The

Civil War had seriously depleted the family fortune and it was

equally disastrous for his boss, Alexander Popham, both suffering

defeat by Royalist troops at the battle of Devizes in 1643. After

this they appear to have retired from the conflict. The

office of Custos Rotulorum was filled by Alexander Popham, who is

described as Keeper of the Rolls of the County at the Wells Sessions,

1653-4.

So the atmosphere at

home was likely to have been sober and industrious with little time

for frivolity. Nevertheless or even perhaps because of it, it is

clear that Locke junior managed to develop an earthy and somewhat

subversive sense of humour. Having been brought up in a Plymouth

Brethren family, I am aware how humour is used to mitigate an overly

sober environment and I think I can understand how it might have

developed.

One of Locke's best

friends whilst at Pensford was another John. John Strachey was an

equally interesting guy of a long and distinguished line. He lived at

an Elizabethan mansion a few miles across the valley at Sutton Court,

that until comparatively recently, retained its ancient castellated

charm and was occupied by a direct descendant. In fact I retain a

vivid memory of visiting as a child with my father who conversed with

the last Lord Strachey, whilst his Great Dane looked in at me and my

Cardigan Corgi through the back window of the Morris Eight! Sadly on

his death, modern economic necessity required the house be converted

to flats, surrounded by “executive houses”, and with it an

indefinable historic aura of a past age was lost for ever.

Until

1973, Sutton Court was the residence of Sir Edward Strachey

(1882––1973), second Baron Strachie, and last in direct line of

descent from John Strachey, F.R.S.

In his 1922

autobiography, “The Adventure of Living”, John St. Loe Strachey

refers affectionately to Sutton Court, his family home and ancestors.

He writes :

“The beauty and

fascination of the house, its walls, its trees and its memories made

…. so deep an impression upon me that to this hour I love the

place, the thought of it, and even the very name of it, as I love no

other material thing.”

Sutton

Court (an early image)

“I remembered with a

glow of pride that it was on these principles that my family had been

nourished. William Strachey, the first Secretary to the Colony of

Virginia, would I felt, have been a true Whig if Whig principles had

been enunciated in his time, for the Virginia Company was a Liberal

movement. John Strachey his son stood at the very cradle of Whiggism,

for was he not the intimate friend of John Locke? Locke in his

letters from exile and in his formative period writes to Strachey

with affection and admiration.”

Indeed right up to his

death in 1674, the very year Locke made his escape to to the

continent, they maintained their friendship, Locke visiting him

whenever back in Somerset and writing to him whenever away. Many of

the letters having been preserved. Consistently it is his humour and

scepticism that comes through. Just one example will have to do.

Whilst on a Government

mission to Germany, he pokes good-natured fun at a “learned bard in

a threadbare coat and a hat that though in its younger days it had

been black, yet it was grown grey with the labour of its master's

brain … his two shoes had but one heel, which made his own foot go

as uneven as his verses.” And again in relation to a formal

disputation of theologians he records, “the dispute was a good

sport and would have made a horse laugh and truly I was like to break

my bridle”.

As the descendant of a

line of Chew Magna saddlers, who probably sewed leather for Strachey

horses (indeed my four times grandparents were born on the Sutton

estate) I appreciate the allusion.

An early photograph of Sutton Court (and as I remember it)

An early photograph of Sutton Court (and as I remember it)

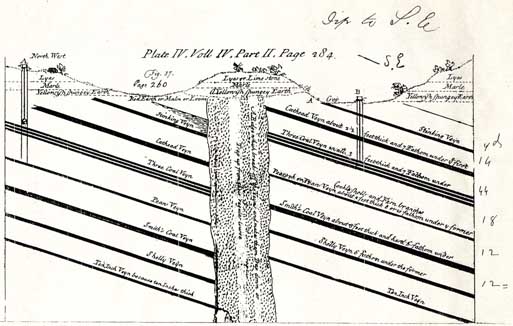

"He

was born in Chew

Magna, England.

He inherited estates including Sutton

Court from

his father at three years of age. He matriculated at Trinity

College, Oxford and

was admitted at Middle

Temple,

London, in 1688. He was elected a Fellow

of the Royal Society in

1719.[1] He

introduced a theory of rock formations known as Stratum,

based on a pictorial cross-section of the geology under his estate

at Bishop

Sutton and Stowey in

the Chew

Valley and

coal seams in nearby coal works of the Somerset

coalfield,

projecting them according to their measured thicknesses and attitudes

into unknown areas between the coal workings.[2] The

purpose was to enhance the value of his grant of a coal-lease on

parts of his estate. This work was later developed by William

Smith.[3] In

addition to his map making and geological interests he had several

other publications including An Alphabetical List of the

Religious Houses in Somersetshire (1731)"

John

Strachey, (born May

10, 1671, Chew Magna, Eng.—died June 11,

1743, Greenwich), early geologist who was the first to

suggest the theory of stratified rock formations. He

wrote Observations

on the Different Strata of Earths and Minerals (1727)

and stated that there was a relation between surface features and the

rock structure, an idea that was not commonly accepted until a

century later.

Sons

and daughters of Sir

Richard Strachey and

Lady Strachey. Left to right: Marjorie, Dorothea,Lytton,

Joan Pernel, Oliver,

Dick, Ralph, Philippa, Elinor, James.

PART 2

Leaving

Home and London Schooling.

In 1647 he left home to

attend Westminster School in London, then and now, one of the most

prestigious in the country. Situated in the shadow of Westminster

Abbey and the Palace of Westminster - the seat of the British

Parliament – the contrast with his rural background must have been

dramatic.

Westminster School

We

know little or nothing about his formal education up to fifteen.

Maybe a local tutor was employed. In any event it could not have been

inadequate preparation for the new school as Locke excelled in Latin

and Greek and was appointed a “King's Scholar” - a privilege

that went to only select number of boys, who from the time of Henry

VIII,

were financed from the royal purse.

When

he was there, the notorious Dr Busby was headmaster who

established a reputation, as much for the birch and strict discipline

as for rigorous classical learning. On the day of Charles I

execution, not many yards away in Whitehall, Busby prayed for the

safety of the King, and then locked the boys inside to prevent their

going to watch the spectacle. He apparently thrashed Royalist

and Puritan boys alike without fear or favour. Busby remained in

office throughout the Civil War and the Commonwealth, when the school

was governed by Parliamentary Commissioners, and well into the

Restoration. Locke

came from devoutly Puritan stock, but he welcomed the return of the

King a decade later. He was comfortable with monarchy, subject to it

being protestant and constitutionally accountable to Parliament, a philosophical position that would subsequently give him big trouble.

After

Westminster, by dint of effort, seeking influential support and an

impressive public oration in Latin, Greek and Hebrew, he secured a

scholarship to attend Christ Church, Oxford, which he entered in

1652.

In 1656 he graduated with a Bachelor's degree and a Master's in 1658. He was subsequently awarded a bachelor of medicine in 1674 despite university opposition, by the intervention and support of his powerful patron, the Earl of Shaftesbury.

Since the late 1650's, including the times he was in Pensford, medicine had been his chosen subject, in preference to the more usual Theology. In fact he did not follow the accustomed route in either and claimed his medical degree on the basis of a proven track record, and especially by the reportedly saving Lord Ashley's life. This rather than the prescribed course of study.

This is not to suggest his own intellect and study did not make up for it. Note books still exist of what we might call “country cures” from his Somerset home and amongst his voluminous writings fragments survive of a manuscript entitled “Arte Medica” that was not published until the 19th Century in Fox Bourne's “Life of John Locke”.

I happen to have A. G. Gibson's 1933 book on the subject. It might today be regarded as guidelines in diagnosis and treatment for a doctor in “general practice”. Reading it, one is impressed with its common sense and modernity. Had it been published, Gibson suggests it might have done for the body, what his “Essay on Understanding” did for the mind.

In 1656 he graduated with a Bachelor's degree and a Master's in 1658. He was subsequently awarded a bachelor of medicine in 1674 despite university opposition, by the intervention and support of his powerful patron, the Earl of Shaftesbury.

Since the late 1650's, including the times he was in Pensford, medicine had been his chosen subject, in preference to the more usual Theology. In fact he did not follow the accustomed route in either and claimed his medical degree on the basis of a proven track record, and especially by the reportedly saving Lord Ashley's life. This rather than the prescribed course of study.

This is not to suggest his own intellect and study did not make up for it. Note books still exist of what we might call “country cures” from his Somerset home and amongst his voluminous writings fragments survive of a manuscript entitled “Arte Medica” that was not published until the 19th Century in Fox Bourne's “Life of John Locke”.

I happen to have A. G. Gibson's 1933 book on the subject. It might today be regarded as guidelines in diagnosis and treatment for a doctor in “general practice”. Reading it, one is impressed with its common sense and modernity. Had it been published, Gibson suggests it might have done for the body, what his “Essay on Understanding” did for the mind.

It was therefore the

move from Somerset to London at age fifteen that was undoubtedly one

of the most significant events in his long life.

Apart from brief periodic visits up to the mid-1660's, he would never return permanently to his Somerset roots, though he retained his local accent - which we must assume was reasonably precise and articulate yet retaining the North Somerset/Bristolian burr - and grounded attitude.

His status was certainly elevated by virtue of his education and employment by aristocracy and Crown, and he died a very rich man by standards of the time, though he was never formally honoured or Knighted. He died as he had lived, just plain John Locke. Indeed it was some years before his impact was truly assessed and acknowledged.

Apart from brief periodic visits up to the mid-1660's, he would never return permanently to his Somerset roots, though he retained his local accent - which we must assume was reasonably precise and articulate yet retaining the North Somerset/Bristolian burr - and grounded attitude.

His status was certainly elevated by virtue of his education and employment by aristocracy and Crown, and he died a very rich man by standards of the time, though he was never formally honoured or Knighted. He died as he had lived, just plain John Locke. Indeed it was some years before his impact was truly assessed and acknowledged.

London, Oxford and

Essex.

After Pensford his life

was spent in London, Oxford, extended periods in France and Holland

and finally Essex, where in 1691, Locke's close friend Lady Masham

(nee Damaris Cudworth) who he had first met in 1681 when she was in

her early twenties and twenty eight years his junior, invited him to

join her at Sir Francis Masham's country house in “Oates”, in

Essex.

She was the daughter of a contemporary at Christ Church and it is difficult not to believe he was smitten by her. In fact they exchanged love letters as “Philander” and “Philoclea”, some of which are still in the Lovelace Collection, so clearly this was not merely a practical solution, though it is impossible to determine the exact nature of their relationship, then or later.

She was the daughter of a contemporary at Christ Church and it is difficult not to believe he was smitten by her. In fact they exchanged love letters as “Philander” and “Philoclea”, some of which are still in the Lovelace Collection, so clearly this was not merely a practical solution, though it is impossible to determine the exact nature of their relationship, then or later.

From Oats, for a while

he made forays to London to fulfil his government job as Commissioner

for Trade until his health could support it no longer. Can you imagine the difficulty and discomfort, given the state of coach suspension and road surface of the time?

He could not cope with London smoke and the stress of business but missed company, lacking intellectual stimulation. In letters he implored friends and relations to visit, saying to one: “Do not think now that I am grown either stoic or mystic. I can laugh as heartily as ever, and be in pain for the public as much as you. I am not grown into a sullenness that puts off humanity – no nor mirth either. Come and try...”

He could not cope with London smoke and the stress of business but missed company, lacking intellectual stimulation. In letters he implored friends and relations to visit, saying to one: “Do not think now that I am grown either stoic or mystic. I can laugh as heartily as ever, and be in pain for the public as much as you. I am not grown into a sullenness that puts off humanity – no nor mirth either. Come and try...”

Locke never married or

had children. Having dabbled with fame, power, intrigue and

influence, one gets the impression in his final decade, he achieved a

certain degree of national respect for his writings and part in the

establishment of a protestant-enshrined new relationship between

Monarch and Parliament. In a sense he came full circle to his

Puritanical and liberal roots as exemplified by his self-composed

epitaph in All Saints Church of High Laver, Essex:-

“Stop, Traveller!

Near this place lieth John Locke. If you ask what kind of a man he

was, he answers that he lived content with his own small fortune.

Bred a scholar, he made his learning subservient only to the cause of

truth. This thou will learn from his writings, which will show thee

everything else concerning him, with greater truth, than the suspect

praises of an epitaph. His virtues, indeed, if he had any, were too

little for him to propose as matter of praise to himself, or as an

example to thee. Let his vices be buried together. As to an example

of manners, if you seek that, you have it in the Gospels; of vices,

to wish you have one nowhere; if mortality, certainly, (and may it

profit thee), thou hast one here and everywhere.”

Revolutionary

Times.

The period Locke lived

through was not without its momentous events, bloody conflicts and

political developments, as ideas clashed with ideas and cohort with

opposing cohort. King against Parliament. Town against Country.

Merchant against Aristocracy. Levellers versus those that believed in

hierarchy. Rich against poor. Tolerance versus Conformity.

Superstition versus Reason. Protestant against Catholic. Anglican

versus Non-conformist. Puritan versus Quaker and Shaker. “Whig”

versus “Tory”. Stuart line versus House of Orange replacement.

Religion and the role

of the King which were inextricably linked, were dominant themes. On

the one hand, the belief all executive power resided in the Monarch

who obtained such authority from the Creator itself. On the other,

that power resided ultimately in the people. It, and the power to tax

without Parliamentary consent, was at the root of the civil war that

lasted, on and off, for most of the 1640's - until King Charles I

lost his head on a bitterly cold January morning in 1649. Regicide –

a crime so unthinkable, the crowd let out what an observer described

as, “a moan as he had never heard before and desired he might never

hear again". Handkerchiefs were dipped in the king's blood as a

memento. It is even possible that Locke and the other Westminster

scholars, despite the efforts of the Headmaster, got an inkling of

it!

Locke's life also

spanned an absolutely pivotal period in human exploration,

colonisation and experimentation. It effectively marks the start of

science as we know it, which progressively affected humanity's world

view. From being central to the divine creation and plan both

literally and metaphorically, the role God played was gradually

pushed back by discoveries through microscope and telescope, by

observation, measurement, experiment and exploration. Having created

the “clock”, God was likened to the Clock Maker. The Bible

account was being tentatively challenged. From the fundamentalist

literal view of the Bible, Locke moved inexorably towards a nuanced

and deist interpretation by virtue of his own reasoning, whilst still

retaining an evangelical view of Jesus as redemptive Christ and

Saviour. Reason versus Faith or conversely Reason supportive of

Faith, resulted in public debate with clerical critics in his later

years.

In Italy in 1642, when

Locke was ten, in far-off Italy, Galileo Galilei, who had been forced

by the Catholic Church's Inquisition to recant his assertion that the

sun, not the earth, was at the centre of the solar system, died. In

the very same year, the great Isaac Newton was born. These two

historical figures mark a huge transformation from the old to the

new, what may be described as a scientific and religious revolution.

The first truly

scientific society, the English Royal Society - still of course in

existence - was founded in 1660, composed of some of the most

enquiring minds of the day. Among the original Fellows were

Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, Robert Boyle, and Robert Hooke. Some

later notables were John Flamsteed, Edmond Halley and Hans Sloane.

John Locke was to be elected to Fellowship in 1668 and moved in these

circles.

Whilst on Somerset trips in the mid-1660's, Locke contributed directly to Boyle's experiments on pressure, and was an assiduous collector of meteorological information for the greater part of his life. He was interested in all things human and all things scientific, what was then referred to as Natural Philosophy. He was well versed in the Classics, could speak at least seven languages and was fascinated with archaeological remains as with the pre-historic Stanton Drew Stone Circle close to his home that he described and discussed with John Evelyn. He was a respected lecturer and tutor in Latin and Greek, a trusted surgeon and physician, a confidant and adviser to political activists at the highest level. In short an undisputed polymath.

Whilst on Somerset trips in the mid-1660's, Locke contributed directly to Boyle's experiments on pressure, and was an assiduous collector of meteorological information for the greater part of his life. He was interested in all things human and all things scientific, what was then referred to as Natural Philosophy. He was well versed in the Classics, could speak at least seven languages and was fascinated with archaeological remains as with the pre-historic Stanton Drew Stone Circle close to his home that he described and discussed with John Evelyn. He was a respected lecturer and tutor in Latin and Greek, a trusted surgeon and physician, a confidant and adviser to political activists at the highest level. In short an undisputed polymath.

Robert

Hooke's Microscopic Flea.

But Locke is chiefly

remembered for his philosophical writings on economics, government

and education at a time of great political upheaval and growth in

trade, commerce, technical innovation and global expansion east and

west. In all of these Locke had a prominent and direct involvement.

Furthermore it now appears that the writings for which he famous

published in or about 1690, were in fact drafted in the early 1660's

which equates to an extended stay in Somerset when his father was

ill. So it it is not altogether fanciful that Locke's quill dipped

initially in Pensford ink!

Personal

Consequences of War.

When Locke was still a

youth at home in Pensford, Britain was wracked by civil war. His

family was directly affected. His father was a country attorney and

land steward for the local Lord of the Manor, Alexander Popham, who

also was appointed a Colonel for the Parliamentary, and ultimately

victorious, forces under Oliver Cromwell. John's father was a Captain

of Horse and was impoverished by it. It was this connection, possibly

by way of gratitude, that Locke secured his Westminster place in 1647, the

Parliamentarians then being in the ascendancy and Popham having the

right to sponsor.

Oxford.

At Christ Church,

perhaps Oxford's most prestigious college, Locke immersed himself in

logic and metaphysics, as well as the classical languages. After

graduating in 1656, he returned to Christ Church two years later for

a Master of Arts, which led in just a few short years to Locke taking

on tutorial work at the college.

His bachelor of medicine awarded in 1674 resulted from influential political connections despite University objections, principally Lord Ashley – later Earl of Shaftesbury - who's life he had saved in a surgical procedure and who's personal physician and confident he became. In 1678 Shaftesbury was made chancellor and Locke became his “Secretary of Presentations”. They were close and Locke's fortunes mirrored those of his master.

His bachelor of medicine awarded in 1674 resulted from influential political connections despite University objections, principally Lord Ashley – later Earl of Shaftesbury - who's life he had saved in a surgical procedure and who's personal physician and confident he became. In 1678 Shaftesbury was made chancellor and Locke became his “Secretary of Presentations”. They were close and Locke's fortunes mirrored those of his master.

Christchurch,

Oxford.

Lord

Ashley, Later Earl of Shafesbury

Anthony

Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury PC (22

July 1621 – 21 January 1683), known as Anthony

Ashley Cooper from

1621 to 1631, as Sir

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Baronet from

1631 to 1661, and as The

Lord Ashley from

1661 to 1672, was a prominentEnglish politician

during the Interregnum and

during the reign of King

Charles II.

A founder of the Whig party,

he is also remembered as the patron of John

Locke.

Cooper

was one of twelve members of parliament who travelled to the Dutch

Republic to

invite King

Charles II to

return to England. Shortly before his coronation, Charles created

Cooper Lord Ashley, so when the Cavalier

Parliament assembled

in 1661 he moved from the House

of Commons to

the House

of Lords.

He served asChancellor

of the Exchequer,

1661–1672.

Lord

Chancellor 1672–1673.

He was created Earl

of Shaftesbury in

1672. During this period, John

Locke entered

Ashley's household. Ashley took an interest in colonial ventures and

was one of the Lords Proprietor of the Province

of Carolina;

in

1669, Ashley and Locke collaborated in writing the Fundamental

Constitutions of Carolina.

Shaftesbury,

who sympathised with the Protestant Nonconformists,

briefly agreed to work with the Duke of York, who opposed enforcing

the penal laws against Roman Catholic recusants.

By 1675, however, Shaftesbury was convinced that Danby, assisted by

the bishops of the Church of England, was determined to transform

England into an absolute

monarchy,

and he soon came to see the Duke of York's own religion as linked to

this issue. Opposed to the growth of "popery and arbitrary

government", throughout the latter half of the 1670s Shaftesbury

argued in favour of frequent parliaments (spending time in the Tower

of London,

1677–1678 for espousing

this view) and argued that the nation needed protection from a

potential Roman Catholic successor to King Charles II. During

the Exclusion

Crisis,

Shaftesbury was an outspoken supporter of the Exclusion

Bill,

although he also endorsed other proposals that would have prevented

the Duke of York from becoming king, such as Charles II's remarrying

a Protestant princess and producing a Protestant heir to the throne,

or legitimising Charles II's illegitimate Protestant son the Duke

of Monmouth.

TheWhig

party was

born during the Exclusion Crisis, and Shaftesbury was one of the

party's most prominent leaders. In

1681, during the Tory reaction

following the failure of the Exclusion Bill, Shaftesbury was arrested

for high

treason,

although the prosecution was dropped several months later. In 1682,

after the Tories had gained the ability to pack London juries with

their supporters, Shaftesbury, fearing a second prosecution, fled the

country. Upon arriving in Amsterdam,

he fell ill, and soon died, in January 1683.

Flight

and Fight.

When Shaftesbury fell

out of favour, when he was implicated in an assassination attempt on

the King – the so-called Rye House Plot – in 16, Locke made a run

for it to Holland where he laid low for several years. He may well

have been supportive of, and instrumental in, the “Monmouth

Uprising” in 1685, that ended disastrously for the participants –

Locke's Somerset countrymen. He may even have known the families on

his Pensford estate from which twelve men were hung and many more

sentenced to transportation.

James

Duke of Monmouth and Buccleuch 1649-85:

Portrait and Contemporary Image of his Execution and of West Country

Rebels

The narcissistic Duke

of Monmouth was executed, as were many of his followers after the

“Bloody” travelling Assize, supervised by the young but vicious

Judge Jeffreys. There is little doubt that the two events of Civil

War and the Monmouth Uprising were crucial factors in his political

stance and writings. He witnessed first hand the destructive power of

religious and political intolerance, and the cold viciousness that

could be meted out by Government against its own people. Privately he

may also have felt a stab of guilt for his part in a disastrous and

bloody rebellion.

Shaftesbury's

Downfall

Locke, despite his best

efforts, or perhaps because of them, had a habit of courting

controversy and danger. As a result he also became adept in the arts

of subterfuge, camouflage and discretion. In correspondence he

developed his own short-hand and code. In 1660 when the issue of the

Restoration of Charles the Second was being decided, and vengeance

being meted out to those that supported his execution of his father,

Locke returned to, some might say “laid low” in, Somerset until

the issue had been decided and he could return to Oxford, untainted.

When his Patron and

employer fell out of favour and lost his job as Chancellor in 1675,

Locke rather conveniently set sail for France for his health – he

suffered all his life from something akin to asthma – and didn't

return for three and a half years. Shaftesbury fled to Holland in

1681 where he died soon after. Locke attended his funeral when his